Here’s How to

![]()

Make Peace and Justice Your Full-Time Job

If all you saw were the headlines about wars, inequality and injustice, you might believe peace is out of reach. Yet amid it all, people near and far are working tirelessly to repair communities, rebuild trust and reimagine systems that serve everyone. Their efforts remind us that peace isn’t passive; it’s created. And it’s sustained by those willing to turn empathy into action. If this sounds like you, a career in the field of peace and justice may be your calling.

Key Takeaways

Peace work addresses conflict, justice and structural change through the Strategic Peacebuilding Pathways model.

People who thrive in peace work share four core traits, such as an interest in lifelong learning.

To create a lasting impact, peace workers need four essential skills, including program design expertise.

.png)

Peace workers can pursue several career paths in various sectors, such as nonprofits, policy and more.

The MA program in Peace and Justice at USD’s Kroc School of Peace combines theory and experiential learning to prepare changemakers for real-world leadership.

What is Peace?

Peace is more than just the absence of violence or fear of violence. It’s the presence of justice, safety and dignity in people’s everyday lives.

Because peace looks different in every context, it’s heavily shaped by individual and collective experiences. What feels like peace to one community may still leave another struggling to be heard or safe. That’s why effective peacebuilding begins with listening, especially to those most affected by conflict and inequality.

Peace work spans three levels. At the heart of peace studies are those who work directly to resolve conflict, such as mediators and negotiators. The second layer includes those who work in similar sectors, such as human rights, gender rights, racial equality and environmental justice. The third layer includes individuals in every profession, such as education and health. Every profession can be an opportunity to promote peace and justice.

Positive Peace vs. Negative Peace, and Other Elements of Peace Studies Theory

In peace and justice studies, negative peace means the absence of violence or fear of violence; it occurs when fighting stops, but deeper tensions persist. Positive peace, or sustainable peace, is the ultimate goal of peace work because it describes the conditions that allow people and societies to thrive through trust, cooperation and equity.

True peace requires both positive and negative peace. Ending violence—whether direct, structural or cultural—is only the first step; lasting peace depends on repairing relationships and addressing the injustices that caused conflict in the first place. Peace and conflict studies must include an analysis of the tools and histories of oppression.

The Eight Pillars of Positive Peace

Positive peace is the result of a number of other underlying social conditions, each of which contributes to a greater whole than the sum of its parts. Working for peace therefore requires understanding each of these components and using a multidisciplinary, holistic approach [Institute, page 10]. The Institute for Economics & Peace defines positive peace according to eight constituent factors.

1 Well-functioning Government

A well-functioning government delivers high-quality public and civil services, engenders trust and participation, demonstrates political stability and upholds the rule of law.

2 Sound Business Environment

The strength of economic conditions and the formal institutions that support the operation of the private sector. Business competitiveness and economic productivity are both associated with the most peaceful countries.

3 Equitable Distribution of Resources

Peaceful countries tend to ensure equitable access to resources such as education, health, and, to a lesser extent, income distribution.

4 Acceptance of the Rights of Others

Peaceful countries often have formal laws that guarantee basic human rights and freedoms, and the informal social and cultural norms that relate to the behaviors of citizens.

5 Good Relations with Neighbors

Peaceful relations with other countries are as important as good relations between groups within a country. Countries with positive external relations tend to be more peaceful, politically stable, regionally integrated, and have better-functioning governments and lower levels of organized internal conflict.

6 Free Flow of Information

Free and independent media disseminates information in a way that leads to greater knowledge and helps individuals, businesses and civil society make better decisions. This leads to better outcomes and more rational responses in times of crisis.

7 High Levels of Human Capital

A skilled human capital base reflects the extent to which societies educate citizens and promote the development of knowledge, thereby improving economic productivity, care for the young, political participation and social capital.

8 Low Levels of Corruption

In societies with high levels of corruption, resources are inefficiently allocated, often leading to a lack of funding for essential services and civil unrest. Low corruption can enhance confidence and trust in institutions.

What Is Peace Work?

Peace work turns theory into action. The Strategic Peacebuilding Pathways model, created by John Paul Lederach and Katie Mansfield, illustrates the breadth of this field and the career paths one can pursue.

The inner circle shows the three major areas of strategic peacebuilding that, together, achieve positive peace:

![]() Prevent, respond to and transform violent conflict.

Prevent, respond to and transform violent conflict.

![]() Ensure justice and healing.

Ensure justice and healing.

![]() Facilitate structural and institutional change.

Facilitate structural and institutional change.

The outer circle of the model highlights sub-areas of practice and career focus within those three areas. In all cases, the areas represent work in the U.S. and internationally. For each of these sub-areas, a variety of individual career pathways emerge, but keep in mind that this list is not exhaustive.

The United States Institute of Peace’s (USIP) definition of peacebuilding includes most of what we see in the Lederach/Mansfield model, adds human rights and refugee resettlement and firmly establishes the need to address root causes in order to build positive peace.

Both the Lederach/Mansfield model and USIP’s definition are just two representations of peacebuilding among many. There are numerous other fields that are direct expressions of peacebuilding or intersectional fields of peace work, such as racial and gender justice, genocide prevention, environmental activism, the arts and more.

Is Peace and Justice the Right Fit for You?

It takes a certain kind of person to successfully help others resolve conflicts and preserve human rights. Fundamentally, you must capitalize on your dissatisfaction with the current state of the world, tap into your desire to improve it as a catalyst for change and stay committed despite slow-moving progress and setbacks.

Accordingly, there are a few common traits among people who typically achieve success in this field. Keep in mind that it is possible to learn and cultivate these skills if you’re interested in peace work.

Grounded and Human-Centered

Peacemakers work to improve human life through empathy, humility, integrity and respect for others’ experiences. They value dignity, listen deeply and approach every situation with a social justice mindset.

Transformation Driven

Effective peacebuilders challenge the status quo. They think creatively, tackle deep-rooted problems and design solutions that lead to lasting structural change.

Thirst for Knowledge

Peace work is a lifelong process of learning and unlearning. Practitioners stay curious, informed and open to new perspectives that help prevent harm and strengthen justice.

Team Oriented

Peacebuilding depends on collaboration. Strong communicators who value teamwork, active listening and shared goals help turn individual efforts into collective progress.

Law Stands as the Foundation of Justice

Laws establish responsibility and define justice, serving as a backbone of stable societies. In domestic and international settings, legal frameworks ensure that individuals, governments and institutions operate within just and ethical boundaries.

For example, constitutional law protects human rights and civil liberties. Landmark cases such as Brown v. Board of Education in the U.S. Supreme Court demonstrate how legal decisions can drive societal change, dismantle institutional discrimination and protect the equality of individuals and populations. Though it began as enforcement and accountability, the law was able to set in motion a level of justice that thrust America into a new era of equality.

On a global scale, international law holds nations accountable for maintaining peaceful relations among themselves and within their governance, upholding the freedom of their citizens.

Motivations and Goals of Peace Workers

People who pursue peace and justice come from diverse backgrounds, but they share a common drive: to leave the world better than they found it. Many are drawn to the field out of compassion and a desire to reduce harm, while others are motivated by personal experiences with violence, conflict or inequality that inspire them to change the systems causing those harms.

Some focus on specific issues—from access to clean water or affordable housing to human rights and anti-trafficking efforts. Others channel their energy into rebuilding trust within their own communities or advancing justice on a global scale.

Wherever they work, peacebuilders are united by a belief that change is possible and a commitment to turning that belief into action.

Communication Skills

Peace workers must be strong communicators. They’re able to actively listen, read nonverbal cues and convey complex ideas clearly across cultures and contexts. In mediation, negotiation or advocacy, they are assertive yet diplomatic in order to draw out what needs to be said with respect and sincerity.

Human AND Leadership Skills

Peacebuilding depends on connecting fighting factions and restoring dignity. These skills include mediation, community organizing and calm leadership in high-pressure situations. Whether guiding post-conflict reconciliation, tackling environmental justice or addressing housing inequality, peacebuilders help others find common ground and adapt to change through understanding and trust.

Analytical skills

Peacebuilders analyze the roots of violence and injustice to design actionable solutions. This includes conflict and policy analysis, strategic planning and systems thinking. For those who work with government or political leaders, strong analytical skills are essential to translate moral goals—such as safety or equality—into effective public policy.

Program design AND management skills

Peace work involves designing, monitoring and evaluating peacebuilding programs. Practitioners adapt based on outcomes, manage teams and budgets and leverage storytelling to raise awareness and funds for peacebuilding efforts. These skills turn bold ideas into sustainable impact.

Fortunately, the Kroc School of Peace Studies offers a dedicated program that provides these specific skills and more, as well as the hands-on experiences needed to succeed in peace work. The two-year MA in Peace and Justice is tailored to the individual's career aspirations. Candidates leave the program with the confidence and portfolio to make a definite contribution to peace in the world.

Employment Breakdown: Industries, Job Titles, Salaries, and Growth Opportunities

Peace and justice professionals are needed around the world in various sectors, including nonprofits, government, education, policy, law, humanitarian aid, international development and more.

Below are examples of common roles across key focus areas. Salaries and advancement potential vary depending on the organization’s size, location and funding model, but the demand for skilled peacebuilders continues to grow worldwide.

Peace & Conflict

Qualcomm Employee Relations Specialist

Average Salary:

$72,000 - $109,000

Conflict Mediator

Average Salary:

$65,977

Careers in Structural and Institutional Change

Civil Rights Defense Litigation Attorney

Average Salary:

$150,000 - 200,000

Staff Attorney

Average Salary:

$83,787

Peace & Justice

Advocacy Program Manager

Average Salary:

$68,000 - 70,000

Community Organizer

Average Salary:

$79,000

Strategic Communications and Content Creator

Average Salary:

$80,000

Careers in Violence Prevention & Transformation

Human Rights Officer

Average Salary:

$73,851

Programs Officer

Average Salary:

$100,000

Peace and Justice FAQs

How can we create and maintain peace?

What are examples of positive peace in practice?

What is the goal of peace and justice studies?

What kind of jobs can peace and justice graduates pursue?

What is the Kroc School of Peace Studies known for?

.png)

Looking Ahead: Sector Growth

Current issues will continue to drive the missions of organizations dedicated to peace and justice. For example, job opportunities related to climate change, public health and changing systemic injustices in the United States are already expanding in response to recent events. In addition to the direct impacts of fire and floods, climate change is affecting immigration and food security patterns. As long as there is conflict, there will be a need for effective peacebuilders.

Many peace and justice scholars go on to work in the nonprofit and NGO sectors, which continue to play a vital role in driving social innovation, delivering services and promoting justice-centered work. Over the past two decades, 501(c)(3) nonprofit employment has grown more than 30%. Moreover, 53% of nonprofit employers plan to expand their teams, citing rising demand and new funding opportunities.

This bodes well for individuals seeking a career in the nonprofit world. For those already working in the governmental, private or nonprofit sector, this growth can also translate into greater opportunities for promotions within other organizations.

Kroc School Graduates Advancing Their Peace and Justice Careers

Kroc School graduates are leading change across sectors and around the world. Most alumni work in nonprofit organizations, with many others serving in government, education, international development and private consulting. Their roles span conflict resolution, human rights, community engagement, policy, humanitarian aid, public health, environmental justice and beyond.

Our alumni leverage the skills they gained through the MA in Peace and Justice in positions that range from front-line roles in grassroots organizations to executive leadership in corporate social responsibility departments to founding and running their own organizations.

Below is not an exhaustive list of where or how our alumni are making an impact, but rather a snapshot of the many possibilities an individual can take to advance their career with a master’s degree from the Kroc School.

Job Titles of Kroc School Graduates

- Restorative Justice Practitioner

- Local Government Official

- Homeless Services Manager

- Policy Analyst

- University Professor

- Lawyer

- Fundraising and Development Director

- Grassroots Organizer

- Community Services Director

- Environmental Justice Advocate

- Curriculum Development Fellow

- Human Trafficking Caseworker

- Mediation Consultant

- Tribal Services Liaison

- Immigration/Refugee Advocate

- Executive Director

- Foundation Manager

Real-World Impact: Alumni Stories

When John Patterson received his MA in Peace and Justice Studies from the Kroc School in 2013, he could hardly guess what the future held. He had already established a history of service during seven years in the United States Navy. After leaving the Kroc School, he worked with the Geneva Center for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces. His focus at the Center was private security governance. He also worked with Edify, a non-governmental agency addressing education reform globally.

For the past six years, he has worked with USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA). He most recently served as the Regional Advisor for Europe, the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia. In that role, he was responsible for programming in the Balkans, Caucasus, Central Asia, Israel and the West Bank/Gaza. Under his leadership, USAID continues to meet critical humanitarian needs in Ukraine experienced as a result of the ongoing conflict. They also provide disaster risk reduction programming in these regions, ensuring that communities are better prepared for potential disasters.

Prior to that, as Deputy Team Leader for the Venezuela Regional Crisis Response Team, he helped to manage the U.S. aid response to the crisis in Venezuela. According to the U.S. State Department, more than 9 million Venezuelans are at risk of starvation, and more than 11 million were displaced by force. For his leadership in the response to this crisis, he was recently honored with the Author E. Hughes Career Achievement Award by the Kroc School.

After Amanda Brown earned her MA in Peace and Justice Studies from the Kroc School in 2020, she founded AB LiveWell (ABL), a nonprofit organization committed to preventing violence through holistic advocacy. Her firm partners with credible messengers, strengthens government-community relations and leverages restorative practices. AB Livewell’s goal? For society to realize that individuals with a criminal history, background or organized crime affiliations can transform their lives and contribute to society.

“We have to be trusted by those we consult,” Amanda says. The work begins with deep listening—learning histories and understanding systems—to create safe spaces for stakeholders to have hard conversations with compassion and drive change.

An early project, “No Shots Fired” with the City of San Diego, shows how this approach works in practice. The ABL team began by building trust with the program’s executive director and other credible messengers to implement restorative practices. When pressure from city systems created setbacks, Amanda’s team rebuilt trust with credible messengers through 1:1 conversations, apologies and advocacy, ensuring the program stayed rooted in community needs. ABL’s persistence led to renewed unity among city partners, including police leadership, and contributed to reductions in gang violence.

Amanda’s pathway was shaped at the Kroc School, where she honed skills in mediation, evaluation and conflict analysis, participated in global practicums each semester and interned with the San Diego Mayor’s Office. These opportunities allowed her to build her network and work alongside the Executive Director of the Gang Commission, enabling her to better understand systems. “Diving into all of these experiences made me realize I didn’t want to work for the government or a nonprofit; however, I wanted to be a bridge and a partner to all entities because it’s needed to build safer communities,” she reflects.

Her advice for the next generation of peacebuilders? Take care of your health holistically and “surround yourself with others that have optimism, humility and courage, and allow yourself to feel through it all. You got this!”

After Amanda Brown earned her MA in Peace and Justice Studies from the Kroc School in 2020, she founded AB LiveWell (ABL), a nonprofit organization committed to preventing violence through holistic advocacy. Her firm partners with credible messengers, strengthens government-community relations and leverages restorative practices. AB Livewell’s goal? For society to realize that individuals with a criminal history, background or organized crime affiliations can transform their lives and contribute to society.

“We have to be trusted by those we consult,” Amanda says. The work begins with deep listening—learning histories and understanding systems—to create safe spaces for stakeholders to have hard conversations with compassion and drive change.

An early project, “No Shots Fired” with the City of San Diego, shows how this approach works in practice. The ABL team began by building trust with the program’s executive director and other credible messengers to implement restorative practices. When pressure from city systems created setbacks, Amanda’s team rebuilt trust with credible messengers through 1:1 conversations, apologies and advocacy, ensuring the program stayed rooted in community needs. ABL’s persistence led to renewed unity among city partners, including police leadership, and contributed to reductions in gang violence.

Amanda’s pathway was shaped at the Kroc School, where she honed skills in mediation, evaluation and conflict analysis, participated in global practicums each semester and interned with the San Diego Mayor’s Office. These opportunities allowed her to build her network and work alongside the Executive Director of the Gang Commission, enabling her to better understand systems. “Diving into all of these experiences made me realize I didn’t want to work for the government or a nonprofit; however, I wanted to be a bridge and a partner to all entities because it’s needed to build safer communities,” she reflects.

Her advice for the next generation of peacebuilders? Take care of your health holistically and “surround yourself with others that have optimism, humility and courage, and allow yourself to feel through it all. You got this!”

These are just two stories. We have more than 500 changemakers working in nearly 100 countries around the world. Our students are employed with some of the most influential modern peace-building organizations. This is an impact you can measure and feel.

How USD's Kroc School Amplifies Your Intention to Bring About Peace

At the Kroc School, we turn your commitment to justice into professional impact. As the first stand-alone peace school in the U.S., our MA in Peace and Justice attracts people from around the world who are dedicated to building more equitable communities.

Our engaging courses combine theory and practice — we foreground the deep insights and skill-building that can only be gained from hands-on experience. And, as practitioners of peace themselves, our faculty members draw from firsthand experience when they speak to the most effective approaches for shaping more peaceful and just societies.

Through the Kroc Institute for Peace and Justice (Kroc IPJ), students also collaborate with practitioners and changemakers from around the globe to end cycles of violence and strengthen communities.

Experiential Learning

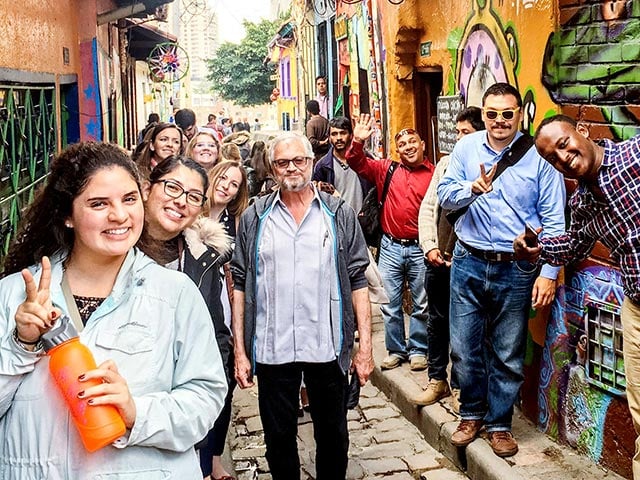

Learning here extends far beyond the classroom. Specifically, students gain real-world experience through experiential learning opportunities in locations such as Mexico, Colombia and Rwanda, where they work directly with local peace practitioners who support displaced people or help rebuild after conflict.

Moreover, students who have an idea for addressing a specific social issue can receive mentorship, access to resources and guidance to create a sustainable business solution through the Fowler Global Social Innovation Challenge. Through this experience, students have the opportunity to pitch their social venture to a group of experts, and can also earn up to $75,000 in seed funding to bring their idea to life.

MA in Peace and Justice Program Overview

Program Length

- 24 months (full-time)

- Flexible part-time options

Curriculum Focuses

- Conflict analysis

- Human rights

- International systems

- Economic development

Applied Learning

- Field-based courses abroad (e.g., Armenia, Mexico and Rwanda)

- A 250-hour internship

Dual Degree Option

JD/MA in Law and Peace and Justice for those interested in:

- Immigration, human rights or mediation issues

- Advising a global clientele

- Influencing policy

Featured Courses

-

Foundations of Peace, Justice & Social Change

-

Peace & Conflict Analysis

-

International Justice and Human Rights

-

Environmental Peace and Justice

-

Human Rights Advocacy

-

Program Design, Monitoring & Evaluation

Electives

Explore your personal interests by taking courses aligned with other master’s programs, such as:

-

MA in Social Innovation

-

MS in Conflict Management and Resolution

Outcomes

Graduates lead in NGOs, government, humanitarian work, education, policy, and advocacy roles.

Internships

Our students have gained valuable hands-on experience through internships with esteemed organizations around the world, such as:

![]() California Innocence Project

California Innocence Project

![]() Casa Cornelia Law Center

Casa Cornelia Law Center

![]() Center for American Progress

Center for American Progress

![]() International Rescue Committee (IRC)

International Rescue Committee (IRC)

While we have a network of peace and justice organizations where students have completed internships in the past, students can also pursue an opportunity with any peace and justice-related organization that interests them. With guidance from their advisor, students decide what kind of experience will best prepare them for a rewarding career in peacebuilding.

Fellowships, Assistantships, and Financial Aid

The Kroc School offers several ways to make graduate study affordable while gaining meaningful experience:

Kroc Practice Fellowships

Become a team member of the Kroc Institute for Peace and Justice and support initiatives related to:

- Cross-border peacebuilding

- Reducing urban violence

- Women, peace, and security

These are paid positions that offer their own merit-based scholarship.

Assistantships

Receive tuition support while working alongside faculty for 40 hours each semester, contributing to research and projects.

Tuition Discounts

- Clergy Members: 50% discount

Peace Corps Volunteers: 50% discount, waived application fee and 6 units of credit - AmeriCorps Alumni and Ashoka U Changemaker Campuses: 25% discount on all Kroc School graduate programs

Scholarships

- All students are considered for merit-based scholarships.

- All incoming students are eligible to apply for private scholarships.

- Students may apply for the need-based USD Graduate Grant.

More than 80% of our students receive some form of scholarship or financial aid, making it possible to focus on what matters most—creating positive change.

Become a Force for Positive Change with a Master’s in Peace and Justice

Building peaceful and inclusive societies does not happen overnight. It takes the commitment of dedicated peace and justice advocates to ensure equal access to justice and significantly reduce incidents of violent conflict. From rural issues in developing countries to addressing urban conflicts, we provide the tools and hands-on experience to help you institute lasting change.

Your journey toward meaningful impact starts here. To learn more about the MA in Peace and Justice program, explore these resources or connect with our team below:

.png)

.png?width=641&height=731&name=Placeholder%20Image%20(3).png)

.png?width=641&height=731&name=Placeholder%20Image%20(4).png)

.png?width=641&height=731&name=Image%20(6).png)