What is Social Innovation?

A Guide For Activists AND Changemakers Interested in

Responsible business and social change

Our world is facing serious challenges today:

from climate change to growing socio-economic inequality, from systemic racism to dealing with the ongoing impacts of the 2020 pandemic — and so many more.

Given where we are, we cannot afford to wait for others to solve the most pressing problems of our time. That is why more and more individuals worldwide are involved in changemaking, working on incredible initiatives that focus on a range of issues: healthcare accessibility, education reform, gender and racial justice, political inclusion, poverty alleviation and workforce development, among many others.

It is clear that our current institutions, systems, and frameworks are not sufficient to address existing problems at local, national, and global levels. Our hyperconnected, complex world demands alternative approaches and new strategies to shape a better future.

- 01 Why Social Innovation and What It Is?

- 02 Tying Social Entrepreneurs, Social Enterprises and Social Innovation Together

- 03 Examples of Social Innovation in Action

- 04 Responding to Social Challenges – Specific Case Studies

- 05 Social Intrapreneurships vs. Social Entrepreneurships

- 06 Why Activists, Changemakers and Entrepreneurs Should Attend The Kroc School's #1 Ranked Social Innovation Program in the Nation

- 07 Pursue Social Change with a Master's in Social Innovation

Table of Contents

- 01 What is Social Innovation?

- 02 The Link Between Social Entrepreneurs, Social Enterprises and Social Innovation

- 03 Systemic Change: Mastering Social Change Through Social Innovation

- 04 What Does Social Innovation in Action Look Like?

- 05 An Inside Look at the #1 Ranked Social Innovation Program at the Kroc School

- 06 Pursue a Meaningful Career Rooted in Social Change with a Master's in Social Innovation

What is Social Innovation?

According to OECD.org, social innovation “refers to the design and implementation of new solutions that imply conceptual, process, product or organizational change, which ultimately aim to improve the welfare and wellbeing of individuals and communities.” In other words, the essence of social innovation is to enact social change and address challenges in businesses and communities alike through new frameworks, services and programs.

Social innovations, aiming to transform the way social needs are met through better-performing solutions, positively affect a wide range of social issues — including community health, education, professional working environments, social development and so many more.

- 01 Why Social Innovation and What It Is?

- 02 Why Social Innovation and What It Is?

- 03 Why Social Innovation and What It Is?

- 04 Why Social Innovation and What It Is?

- 05 Why Social Innovation and What It Is?

- 06 Why Social Innovation and What It Is?

- 07 Why Social Innovation and What It Is?

- 08 Why Social Innovation and What It Is?

For some challenges, it is enough to implement a traditional solution, but for others, no progress toward social change is possible until there is a disruption of the current substandard systems. And social innovation can be an avenue for this disruption.

“DO NO HARM” AND SOCIAL INNOVATION GO HAND IN HAND — HERE’S WHY

We cannot solve what we don’t understand. To propose effective solutions, impact the cause of the problem and avoid doing greater harm, leaders of social change and innovation must understand the root causes of the social injustice or problem in all its complexity.

The principle of “do no harm,” derived from medical ethics, is of utmost importance in creating positive change. For example, when humanitarians are evaluating a proposed solution to a challenge such as a post-natural disaster situation, a diverse stakeholder perspective is required to minimize any potential harm they may inadvertently cause through their actions (such as adding to tensions between communities or creating new ones). In this instance, a diverse stakeholder perspective could consist of people in the affected communities, relief workers, NGO managers and others.

Understanding root causes of problems and ideating viable solutions requires empathy and human-centered design thinking skills. Human-centered design is an approach to problem-solving that develops solutions to problems by involving the human perspective in all steps of the problem-solving process. The goal of the social innovator is to develop effective solutions that result from working with affected communities and gaining a deep understanding of their challenges.

UNDERSTANDING THE LINK BETWEEN SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURS, SOCIAL ENTERPRISES AND SOCIAL INNOVATION

Social entrepreneurs, social enterprises and social innovation are three elements of social change. Respectively, they refer to the person, organization and solution created to accomplish a particular social goal.

Social Entrepreneur

Social Enterprise

Social Innovation

Social entrepreneurs are the changemakers who develop social enterprises — or innovative initiatives and organizations — that solve social, environmental, economic and political problems. What’s key is that these people are entrepreneurial, they see opportunities for change where others don’t, and they harness available resources to make things happen. These visionaries then develop social innovations: the inventions that come from social entrepreneurs and social enterprises.

SOCIAL INTRAPRENEURSHIP VS. SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP: WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE?

-1.png?width=465&height=403&name=190425na_campus-0101%20(1)-1.png)

SOCIAL INTRAPRENEURS:

work within existing companies and organizations with an entrepreneurial mindset to help shift the organization toward more social impact by innovating and launching new initiatives.

.png?width=400&height=346&name=campus_uncropped%20(2).png)

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURS:

create new organizations with social impact at the center of their business models.

If there is one truism about humanity, it is that no one person has all the answers. We need a multitude of changemakers working together across all fields — because many of the most challenging problems humanity is facing can only be solved through collaboration of people from diverse backgrounds.

The opportunities for social entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs are endless. For example, climate change alone has created a plethora of problems, including rampant fires, constant floods and droughts. These problems are already impacting clean water availability and food production, and also driving human migration. Additionally, while we deal with the effects of climate change, we still need solutions in renewable energy and environmentally cleaner production to prevent further damage.

The tech industry is another area of opportunity for social entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs. As our production shifts to automation and artificial intelligence, there will be a great need for solutions that help displaced workers gain new skills and jobs. Furthermore, AI and data analysis advances have already created concerns related to privacy and “deep fake” videos. If left unchecked, issues of this nature can easily challenge the fundamentals of the democratic process.

Every evolving concern, in addition to traditional social challenges, requires new approaches to find effective and efficient solutions.

SYSTEMIC CHANGE: MASTERING SOCIAL CHANGE THROUGH SOCIAL INNOVATION

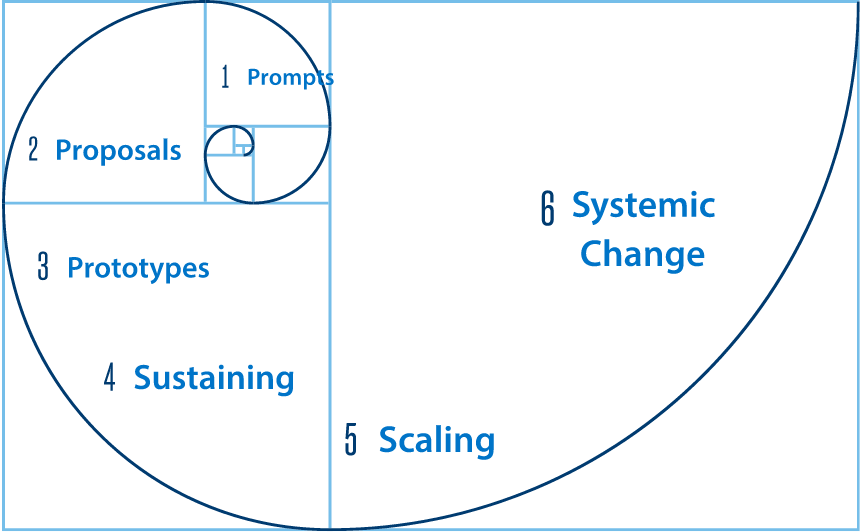

While it may sometimes seem chaotic from the outside, there is a process to achieving systemic change through social innovation.

1. The process begins with prompts, which are inspirations or other occurrences that highlight the need for innovation. An example would be a report chronicling an extremely low graduation rate for a particular high school.

2. Following the prompt, proposals are generated by concerned parties that believe a certain idea or approach will address the problem.

3. During the prototypes stage, each of these proposals is tested and refined to determine the best approach. Sometimes separate ideas will be merged into a holistic program, or the proposals may be ranked by effectiveness.

4. The sustaining stage involves finding ways to continue successful approaches long-term. This can include securing committed benefactors, partners, volunteer pools or other renewable resources. This stage is critical because even the best idea might prove ineffective without long-term support.

5. The scaling stage involves the adoption of the innovation across multiple organizations or across geographies. For example, once Grameen Bank established the efficacy of extending small loans to people in Bangladesh living in poverty (without requiring collateral), micro-finance was leveraged globally by several other organizations.

6. Once the new idea is widespread enough, systemic change begins to happen as the innovation results in new experts, institutions or social norms. Such is the case with micro-finance which, decades after its introduction, is now a fixture of poverty alleviation strategy.

Source: Robin Murray, Julie Caulier-Grice, and Geoff Mulgan, The Open Book of Social Innovation (The Young Foundation, 2010).

WHAT DOES SOCIAL INNOVATION IN ACTION LOOK LIKE?

Creative approaches to solving social problems can occur in any kind of organization. Perhaps the best way to understand the concept of social innovation is to read examples that showcase how it appears in a variety of settings.

Here we will look at social innovation in nonprofits, businesses, B corps, government, education and society.

Social Innovation in Nonprofits

Homeboy Industries was created in East Los Angeles during the height of the 1980s gang and drug epidemics. At the time, young people in gangs or ex-gang members faced little support from institutions. Homeboy Industries innovated to change that with a goal of providing training and career opportunities for former gang members to transform their lives.

Today, they follow a three-part strategy:

1. Standing up for the humanity and rehabilitation of gang members

2. Helping them to heal from their own traumas

3. Investing in their future

In a time when most communities responded to gang members as simple criminals, Homeboy Industries offered an alternative to the traditional prison and law enforcement approach. In 2021 alone, they enrolled 472 former gang members in their 18-month job training program, provided 4,233 gang-affiliated tattoo removal treatments and sponsored 1,833 therapy sessions. Today, the Global Homeboy Network includes more than 400 organizations around the world helping similarly disenfranchised people and providing others with a hopeful future.

Social Innovation in Business

Patagonia started out as a small business operating out of founder Yvon Chouinard’s parents’ backyard and the trunk of his car. An avid climber and outdoorsman from a young age, Yvon had a knack for identifying areas for improvement in his climbing gear.

A pioneer in conscious business, Yvon revolutionized standard attire for the mountaineering community, popularizing new materials that withstood the rigors of climbing and met weather fluctuation requirements, all while retaining their flexibility and functionality. It was at this point that Patagonia became a thought leader in the mountaineering and outdoor recreation space.

But perhaps Patagonia’s greatest claim to social innovation is their sustained effort, from the time they were a small company to now as a large business, to preserve environmental resources and reverse climate change. Patagonia continually exceeds their pledge to environmental responsibility by announcing last year that “Earth is now our only shareholder.” In a letter from Yvon, he states that Patagonia is now using the wealth Patagonia creates to protect the Earth and fight climate change: “Each year, the money we make after reinvesting in the business will be distributed as a dividend to help fight the crisis.”

Social Innovation in Government

Social innovation can be leveraged at every level of government to benefit the populations it serves. One example is former Mayor Michael Tubbs’ initiative to provide universal basic income (UBI) to the people of Stockton, CA — one of only a few U.S. programs of its kind in the last several decades.

Beginning in 2019, Tubbs initiated an 18-month UBI pilot program to increase income stability and offer a financial lifeline to low-income residents. 125 people were chosen to receive $500 per month through February 2021. While the concept of UBI is not new, implementing and studying this program signals social innovation in government for the United States, a country that has traditionally expressed reservations about this kind of system.

However, the Stockton pilot program appears to disprove existing fears about how beneficiaries will spend the income. A preliminary analysis of the reporting data suggests that recipients primarily used the money for necessities (e.g. food, rent, utilities, gas, medical care and emergency situations).

Fundamentally, Mayor Tubbs sees this program as a “rejection of the scarcity mindset,” and an investment in everyday Americans. The success of the program has fueled renewed interest in establishing and studying similar programs across the United States. Currently, more than 40 mayors have joined the Mayors for a Guaranteed Income organization and have pledged to support UBI programs as a means of alleviating poverty and working toward shared prosperity in the U.S.

Social Innovation in B Corps

Innovators (like Patagonia) have pushed for the emergence of benefit corporations (B Corps), which are for-profit companies legally designated as organizations committed to creating public benefit. Unlike other corporations, which are expected to make business decisions primarily with financial profit in mind, B Corps are required to consider the impact of their decisions on additional stakeholders, not just shareholders.

B Corps are also held to additional reporting, transparency and accountability standards. The companies are obligated to publicly release an annual benefit report detailing their overall social and environmental performance based on a third-party standard.

King Arthur Flour is one example of a B Corp that is leveraging social innovation to benefit its stakeholders. King Arthur Flour has been providing high-quality baking staples to professionals and home cooks since 1790, however, what makes King Arthur a truly remarkable company is their commitment to their employees.

In 1996, King Arthur’s owners sold 100 percent of the company to its employees. The owners prioritized maintaining the family-centered work culture and felt that by selling it to their employees, it would “[bring] out the best in people.” The transaction was completed in 2004, and King Arthur became a founding member of the B Corp community in 2007, solidifying “its commitment to all stakeholders: shareholders, business partners, the community and the environment.” Since selling the company to its employees, King Arthur Flour has experienced enormous growth, with annual sales topping $100 million.

Social Innovation in Society

Not all social innovations happen within formal organizations; many begin as changes that are adopted by individuals and groups of people because they are useful in their efforts to create change. This is what we see through the countless innovations made possible by the rise and spread of new digital technologies.

Camera-equipped smartphones are used to document important events and to spread the word about critical social issues. Social media has emerged as an amplifier of some of humanity’s best (and worst) attributes. While there is plenty of innovation in these popular examples, a whole host of technologies are making a difference as well.

Drones, for example, are upending the way we think about space. New research by Kroc School Associate Professor Austin Choi-Fitzpatrick has documented the many ways drones are being used to amplify the voice of the people, and to hold the powerful to account. In his publication, The Good Drone, Choi-Fitzpatrick examines “the way small-scale drones — as well as satellites, kites, and balloons — are used for a great many things, including documenting human rights abuses, estimating demonstration crowd size, supporting anti-poaching advocacy and advancing climate change research.”

Social Innovation in Education

Access to quality education is one of the most fundamental challenges for humanity as well as one of the greatest opportunities for its development. For Khan Academy founder Salman Khan, free access to a quality education became a calling. In 2006, Khan began posting math tutoring videos on YouTube specifically to assist friends and family members. However, it soon became obvious that a large portion of the public wanted online tutoring lessons as well, and on a variety of subjects.

Three years later, Khan Academy was officially incorporated as a nonprofit organization, and Khan quit his hedge fund job to lead the organization full time. After nine months of living off his own savings, he began to receive significant donations that allowed him to build an organization with global reach. In the past decade, Khan Academy has uploaded over 13,000 videos covering more than 400 courses. The company has also registered over 90 million users who speak 40+ languages.

Teachers in elementary schools across the U.S. and globally have used the lessons available on Khan Academy to “flip” their classrooms. Many teachers have assigned students to watch Khan Academy lessons so that they could practice and review the concepts covered in class (what traditionally has been homework). To the delight of teachers, students and parents, Khan Academy is democratizing education and improving it at the same time.

Grassroots solutions, developed by the people experiencing the issue, often prove most effective at tackling the complex and evolving challenges the world is facing. Khan Academy is a perfect example of a decentralized local solution that has been scaled up to solve a massive world challenge.

AN INSIDE LOOK AT THE #1 RANKED SOCIAL INNOVATION PROGRAM AT THE KROC SCHOOL

At the University of San Diego’s Joan B. Kroc School of Peace Studies, we recognize that social innovation is a critical tool in tackling the overwhelming challenges that institutions, organizations and businesses are facing today. We understand that promoting peace and shared prosperity means being able to analyze the root causes of social problems and then, creating and implementing solutions with professionally designed and managed programs that go on to positively impact the lives of people every single day.

In response to this need for mission-driven professionals who go on to impact real social change, we offer a unique field of study:

THE MASTER OF ARTS IN SOCIAL INNOVATION (MASI)

As a student obtaining our master’s in social innovation, you will graduate with the practical skills and experience needed to harness the power of innovation to lead impactful careers.

At the USD’s Kroc School, Associate Professor Austin Choi-Fitzpatrick uses the term social innovation as a way to describe humanity’s ongoing “efforts to develop new (or resurrect old!) ways to make the world a more just, equitable and habitable place.” Professor of Practice Juan F. Roche speaks of social innovation as “any process that develops and deploys effective solutions to systematic social problems, either to solve them or manage them to advance social progress.”

Dammeyer Distinguished Professor of Global Leadership and Education, Paula Cordeiro, also emphasizes that social innovation requires novel thinking — new ideas, processes, strategies or organizational models that can lead to new situations in communities that are much better than what existed before. These professor’s views affirm that the purpose of social innovation is to better meet social needs and advance social progress.

The Master of Arts in Social Innovation is similar to the traditional MBA in that it teaches you to translate business acumen into a meaningful career. You can think of the MASI program as a strategic degree of study that emphasizes social justice while building upon the organizational change skills needed to transform institutions, organizations, businesses and teams that are working towards creating a more sustainable and ethical future.

Note

Another reason to consider the MASI program compared to an MBA? You can earn the Master of Arts in Social Innovation faster than an MBA, and since you will graduate with the niche skills needed to work in unique business environments, you will also experience more career opportunities.

WHERE MASI GRADUATES ARE IMPACTING SOCIAL CHANGE

MASI graduates make global impact through careers leading entrepreneurial ventures, in the public and private sector as well as intergovernmental organizations and nonprofits. Graduates work within organizations focusing on social change and creating economic, social and environmental value within corporate social responsibility departments as well as local, state and national governments.

*This is not an exhaustive list of all graduate employers and doesn't guarantee employment with listed employers.

WHY

YOU SHOULD CHOOSE THE KROC SCHOOL'S

MASI PROGRAM

As a MASI student, you will experience the advantage of integrated expertise in social innovation, entrepreneurship, peacebuilding, business and leadership. Here are a few noteworthy reasons to choose the Kroc School’s MASI program:

NATIONALLY RANKED SOCIAL INNOVATION MASTER’S PROGRAM

NATIONALLY RANKED SOCIAL INNOVATION MASTER’S PROGRAM

NATIONALLY RANKED SOCIAL INNOVATION MASTER’S PROGRAM

EXPERT FACULTY:

Our professors are actively involved in innovative work and research, and as a result, teach from practical, first hand experience. We have a diverse collection of professors and guest lecturers who have created social impact in the U.S. and globally within nonprofits, for-profits, NGOs, B corps and informal settings.

EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING:

To be an effective change leader, one must have the opportunity to apprentice with the problems they will attempt to solve. Through experiential learning and real-world projects, MASI students refine the skills necessary for effective problem identification and problem solving. Students have access to a variety of opportunities to put their learning into action, including a Social Innovation Practicum in which students act as consultants for organizations focused on a particular social issue.

GLOBAL COMMUNITY:

The Fowler Global Social Innovation Challenge provides a direct opportunity for students to earn seed funding for their innovative ideas, and students enrolled in “Kroc 594: Business and Social Innovation” can participate in the Challenge as part of their coursework. Our global community exposes students to a variety of ideas and perspectives that inspires greater cross-sector and cross-cultural collaboration.

WHAT THE MASI PROGRAM WILL OFFER YOU

The MA in Social Innovation is a 30-unit degree program that can be completed in nine months (full-time). Flexible, part-time options are also available. Courses emphasize five learning goals to understand the complexities of social issues, experimentation in design, implementation and impact assessment, design thinking and problem-solving.

Here are just a few of the courses included in the MASI curriculum:

- War, Gender and Peacebuilding

- Business and Social Innovation

- Immigration and Asylum in Practice

- Transitional Justice

- Leadership and Organizations

- Program Design, Monitoring and Evaluation

- Environmental Peace and Justice

Additionally, through opportunities such as the Social Innovation Practicum in which students serve as consultants to organizations tackling specific social issues like homelessness and food insecurity, students gain practical experience and insight that further prepares them to advance their careers.

MASI ADMISSION REQUIREMENTS

The MASI program is an investment in your future success. The program costs an average of $36,000. However, a variety of financial aid, scholarships and tuition discounts are available to reduce the total amount. Future students may also apply for fellowships and assistantships to further reduce their program cost and gain additional experience.

TO APPLY, BE PREPARED TO SUBMIT THE FOLLOWING:

Transcripts

A current resume

Two letters of recommendation

Scores for the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) or the International English Language Testing System (IELTS) for international students*

*Note: This test can be waived under certain circumstances.

Candidates must also provide four short essays and a two-minute video to introduce themselves and explain why they wish to enter the program. We do not require the GRE test to apply to the MASI program.

PURSUE SOCIAL CHANGE WITH A MASTER’S IN SOCIAL INNOVATION

DEFINITIONS AND EXAMPLES

If you have a desire to change the world, you need expertise in social innovation. Your success will depend on finding avenues for change that either have not yet been considered or that need to be reimagined. USD’s Master of Arts in Social Innovation offers the next steps to build or advance your long and fulfilling career in social innovation, founded in impactful and creative leadership.

With expert faculty who have on-the-ground experience, intimate class sizes and ample opportunities for experiential learning, the MASI program will serve as a launching pad for your dream career in social change, social innovation and responsible business.

If you would like to learn more about our Master of Arts in Social Innovation, you have a few options:

If you are ready to bring your entrepreneurial mindset to innovate social change, start your online application!

Related Links

Experience San Diego Majors and Minors Graduate Programs